What does CST have to do with Prison Chaplaincy?

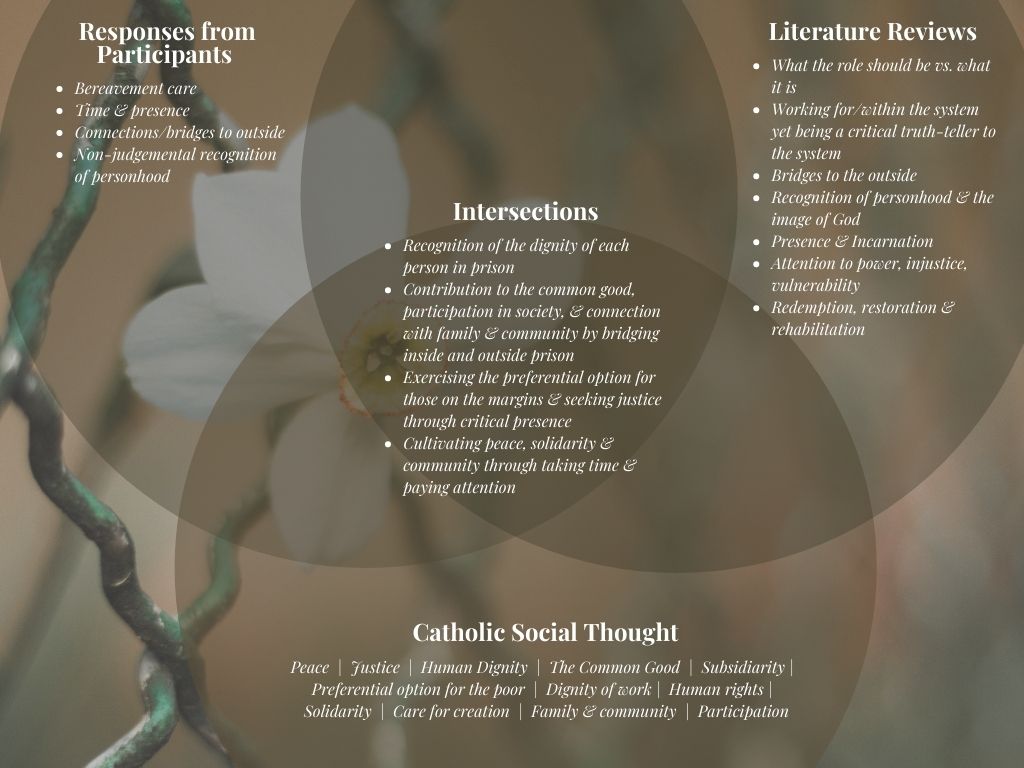

This graphic represents the three areas of research in the Flourishing Inside project:

- Listening to project participants, who included current practitioners of prison pastoral care and former prison residents

- Analysing literature related to prison chaplaincy, including empirical research of chaplaincy, prison chaplaincy, and religion in prisons as well as theological literature about chaplaincy and prisons.

- Analysing Catholic Social Thought, including official documents of Catholic Social Teaching, literature about them, and wider literature on the themes and movements of Catholic social thinking and engagement

Within each of these areas of enquiry, you can see the key themes which emerged from the research, and in the centre of the graphic you can see the key areas where these themes overlapped and intersected. These findings are summarised below, and you can read the full report on the project here.

Catholic Social Thought

For definitions of Catholic Social Teaching and Catholic Social Thought, and for key themes in this literature, see our What is CST? page.

Responses from Practitioners

Through our research day with a focus group of practitioners involved in pastoral care of current and former prison residents, and interviews with former prison residents,[1] several key themes emerged in common about the experiences of prison residents, prison chaplains, and their involvement with prison chaplaincies.[2]

- Bereavement Care: One of the formal duties of all prison chaplains is to visit prison residents when there has been a death in that person’s family. Prison residents spoke of the importance and significance of how chaplains handled bereavement care. This included one who told a story of a service that was organised when a beloved fellow resident committed suicide, another who described the impact of a chaplain who remembered bereavement anniversaries and reached out on those days, and another who received assistance from a chaplain to connect with family members when his mother died. Practitioners spoke of the importance of reliable access to and pastoral care for bereaved prison residents. They also emphasised that this was an area where they lacked and desired formal training.

- Time and Presence: When asked whether involvement with the chaplaincy contributed to their well-being during imprisonment, former residents described appreciating the way chaplains took time to be with them and pay proper attention to them. The importance of taking time was related both to the chaplain taking more time with them than other prison staff, and also to a sense that the time and presence of chaplains was genuine and caring. Practitioners said that having and/or taking time was one of the most important parts of their job. They also said one of their main frustrations was feeling unable to spend the time they wanted to with prison residents, whether in pastoral care or religious provision beyond the standard weekly service. The lack of time was connected to several realities: the demands on their own time, the short time they may have with a resident before release or transfer to another prison, and the lack of time allowed within the prison regime. Practitioners also emphasised the importance of presence, including being there for those who have no one else, being available to support both residents and staff ‘in very difficult working/living environments’, and listening.

- Connections/Bridges to Outside: Former prison residents named connections with people outside as something they most appreciated about chaplains’ work. They described receiving assistance from chaplains in contacting and speaking/corresponding with family, interactions with volunteer groups working with the chaplaincy, and being helped with making contacts for the transition outside upon release. When asked about chaplains who particularly impacted them and how, some participants spoke of chaplains who remained present with them in their release transition. One participant described how he had received no transitional assistance and had no positive connections outside when he was released from his first two sentences, but on his third the chaplain introduced him to his local community chaplaincy, which he believed made all the difference. When asked whether involvement with chaplaincy inside had contributed to their well-being outside since release, those who were not involved with community chaplaincies described the difficulties of having been cut off upon release from the tangible help they received from chaplains inside; whereas those who had been connected to community chaplaincies spoke of their contribution to their current well-being. Practitioners described themselves as having a bridging role between inside and outside, through bringing in volunteers, helping maintain and sometimes mend relationships with family members, connecting prison residents to global Christian fellowship and liturgy, sharing perspectives outside prison of what it is really like inside, and making referrals for assistance upon release.

- Non-judgemental recognition of personhood: In answers to all the questions regarding what they most appreciated about the chaplaincies they’d encountered, how it contributed to their well-being, and what the chaplains who impacted them most had done, there was a consistent and clear cluster of themes related to prison residents feeling recognised and treated as fellow human beings. They described feeling that chaplains empathised with them and did not judge them. They said the chaplains treated everyone equally and took time to treat them as persons. Some spoke of how chaplains demonstrated trust in them (instead of the suspicion which is endemic to the prison context). Practitioners described the recognition of personhood as one of the most important and impactful aspects of their work, including relating to residents as persons, taking their selfhood and agency seriously, and offering unconditional affirmation, love, and acceptance. When asked what motivates them in their work, personhood also emerged. They spoke of accepting all persons, wanting to ‘see and respond to the holiness in each person,’ and recognising them as persons from whom they could learn and draw strength. One practitioner said, ‘we hope that we represent the image of Christ to people, but also we encounter Christ in them, so that transaction is what’s central to what motivates me . . . the more I recognise Christ within the other, I realise how much it’s lacking in me’.

Apart from these overlapping themes between the two participant groups, a few key findings emerged from each group individually.

- When describing what prison chaplains do that is most important and impactful, practitioners placed much more emphasis on sacramental and spiritual practices than did former prison residents, who placed much more emphasis on tangible assistance and advocacy.

- Former prison residents also emphasised the importance of the physical space of the chaplaincy, as a place of peace and solace, and as a place of fellowship and belonging.

- When asked in what ways they felt best equipped and resourced for their work, practitioners responded primarily in terms of working within and relying on a good team within their chaplaincies. When asked in what ways they lacked equipping and resources, what frustrates them most in their work, and what the central difficulties are in their work, the majority of answers related to structural, systemic, and staff issues in the prisons.

- Practitioners emphasised their feelings of lacking time, lacking adequate resources, lacking formal training, and lacking adequate support/management/connections within the prison and in relation to Chaplaincy HQ.

- Practitioners also emphasised their concerns for the wellbeing of residents within the prison system, including issues related to lack of support for vulnerable residents, constant movement between prisons, overcrowding, unnecessary use of force, ‘petty’ rules, lockdowns due to staff shortages, outdated facilities, ‘undignified’ and ‘humiliating’ treatment, rising cases of self-harm, and unreliability of access to pastoral care or religious provision.

- It was notable that although the vast majority of problems, frustrations, needs, desires, and issues the practitioners discussed had to do with structural, systemic, and prison staff realities, when asked what resources they needed and desired, the majority of the answers were liturgical and spiritual.

[1] Eight women attended the research day and six men were interviewed. Original plans for the research were for a much larger and broader group of participants, however the research began in February of 2020 and the first lockdown began shortly after our first research day, which was planned to be the first of a series of collaborative action research events which were made impossible by the pandemic. Plans to visit community chaplaincies and women’s centres to interview additional former prison residents were also made impossible by the pandemic.

[2] Discussions during the research day and all interviews were digitally recorded with permission, transcribed, and coded and analysed using Nvivo software.

Literature Reviews

The reviews of relevant literature for the project included empirical research as well as theological literature related to prison chaplaincy. The full bibliography is available here.

More specifically, the following types of literature were consulted:

- Empirical studies of prison chaplaincy

- Empirical studies of prisons which address chaplaincy and/or religion in prisons

- Theological work on chaplaincy

- Theological work on prison chaplaincy

- Theological work which relates Catholic Social Teaching to prisons

- Documents published by churches in the US and England and Wales regarding prisons

The following key themes emerged from this diverse body of literature:

- There are significant tensions between theologies and theories of what the role of a prison chaplain should be and realities of what the role is or is perceived to be. Prison chaplains spend more of their time on administrative and other tasks which are peripheral to the religious and pastoral provision they consider central (Sundt and Cullen 1998 and 2002; Pew Research Center 2012). Prison chaplains tend to explain their role in religious terms whereas prison officers and residents tend to explain the chaplain’s role in terms of humanitarian assistance (Todd and Tipton 2011; Liebling et. al. 2011). Although prison chaplains believe that extremism is uncommon and not a major threat (Pew Research Center 2012), increased focus on anti-extremism agendas has a significant impact on prison chaplaincy (Todd and Tipton 2011; Todd 2013). A study of one English prison found that the focus of governance in relation to religion was on reducing the perceived risks of extremism rather than encouraging positive faith practices (Liebling, et. al. 2011). One piece on Christian chaplaincy names five theological models according to which chaplains themselves and their churches understand their work, contrasted with five secular models according to which the institutions and publics with whom they work understand chaplaincy (Threlfall-Holmes and Newitt 2011).

- There are significant tensions for prison chaplains between working for and within the system and being a critical truth-teller to the system. Chaplains understand their primary purpose as working for and on behalf of the prison residents, but in reality they often serve the needs and interests of the prison system, including the control of prison residents (Sundt and Cullen 1998 and 2002). Several of the theological sources on the role of chaplains note that the chaplain acts as a critical friend, a prophet, and/or a challenging presence within the institutions where they work. However, in most of the work reviewed this was either mentioned only briefly or in passing, or was not mentioned at all (absence was particularly notable in all the England and Wales training and induction materials for prison chaplains provided by NOMS, the Quakers, the Church of England, and the Catholic Church). By contrast, other theological work focused on critical presence as central to the role of prison chaplaincy (Church of England 1999; Williams 2003; van Eijk et. al. 2016; Todd 2016; DuBois Gilliard 2018). While some emphasise working within the system so as not to be dismissed as troublemakers (Brandner 2014), others argue that ‘when a prison chaplain only adapts to the situation and does not speak out on human dignity violations he loses his identity, his credibility and betrays his vocation’ (van Eijk 2016). One piece in particular emphasises the role of the chaplain as truth-teller, which includes telling prison residents the truth of who they are and telling the prison system itself the truth of how it should function and how it falls short (Williams 2003).

- Bringing in volunteers and other aspects of acting as a bridge between inside and outside were central to literature on the role and work of prison chaplaincy. This includes the importance of volunteers both for prison residents and for enriching the church; the ability of chaplains and those who volunteer in prisons to influence public perception and policy related to prisons; recognising that prison residents are members of society and empowering them to make positive contributions; and helping with transitions during and after release from prison (Kavanaugh 2014; Brandner 2014; Sadique 2016; van Eijk et. al. 2016; Riordan 2020).

- In both secular and theological work, there is a shared emphasis on the importance of the prisoner as person, including humanising residents in dehumanising contexts, recognising each individual’s personhood, upholding human dignity, and the creation of every human in the image of God. Prison residents view chaplains as distinct from prison officers, with one of the distinctions being that chaplains treat the residents as persons (Todd and Tipton 2011). In one English prison, residents viewed chaplains as distinct from prison psychologists, with one of the distinctions being that chaplains demonstrated trust whereas psychologists focused on risk assessment (Liebling et. al. 2011). The same study found that prison residents trusted chaplains and education staff because they believed that they cared for their best interests and viewed them as humans, not merely offenders. The humanising effects of religious conversion in prison include a new sense of identity, meaning, and empowerment (Maruna et. al. 2006). In theological work, prison ministry is said to begin with the centrality of humankind as God’s creation (Hall 2004), to recognise the intrinsic worth of every human being (Kavanaugh 2014), to focus on all people being created in the image of God and the importance of human dignity (Brandner 2014), to contribute to rehumanising those who have been dehumanised by the system (Hake in van Eijk et. al. 2016).

- Theological work emphasised the theme of presence, which was often related to incarnation. There is an entire book dedicated to tracing the dominance of the model of ‘ministry of presence’ to describe chaplaincy, and how this can either be an invocation of incarnational theology which positively engages with pluralism, or a diffuse notion which cannot sufficiently address tensions chaplains experience between accountability to themselves, to their employers, and to their faith communities (Sullivan 2014). Some work emphasises the presence of Christ in the chaplain’s example, in those who are imprisoned, and in the incarnational nature of the ministry (Pope John Paul II 2000; Hall 2004; Sadique 2016; Todd 2016; DuBois Gilliard 2018).

- Prison chaplains were described as those with a special responsibility to pay attention to power, injustice, and vulnerability. These themes were especially prominent in theological literature, and especially where the critical presence of the chaplain was central. Prison chaplains and their churches are called on to challenge institutional racism (Jones and Sedgwick 2002), challenge abuses of power (Hall 2004), to stand on the side of the powerless (Brandner 2014), and advocate for non-custodial solutions for vulnerable populations (Church of England 1999).

- Prison chaplains are also described as being responsible for and/or known in practice for their contribution to work which can be described in relation to redemption, restoration, and rehabilitation. Although overall it cannot be said that research proves a clear link between chaplaincies and desistance, many studies have linked involvement with prison chaplaincies (or religion in prison) with better adjustment and behaviour within prison as well as increasing commitments to rehabilitation (Deuchar et. al. 2016; Clear and Sumter 2002; Maruna et. al. 2006; Levitt and Loper 2009; Duncan 2018). Prison chaplains tend to favour understandings of prisons as rehabilitative rather than punitive (Sundt and Cullen 1998 and 2002; Pew Research Center 2012), and theological work often emphasises that prison ministry which is redemptive also advocates for criminal justice which is rehabilitative and restorative, rather than retributive or retaliatory (Pope John Paul II 2000; Hall 2004; Williams 2003; van Eijk et. al. 2016; CBCEW 2004; USCCB 2000; Conway et. al. 2010; Levad 2011 and 2014).

It is also worth noting how a few findings in empirical research literature intersected with responses from participants of Flourishing Inside.

- Some former residents emphasised that the chapel was an important and safe physical space, as did the respondents in Todd and Tipton’s study (2011).

- There was much discussion between the practitioners who participated in the research day about how they felt that other groups in their prisons, particularly Muslims, have more access to residents, more reliable provision of religious requirements, and/or more resources. An in-depth ethnography of one English prison found that both Muslim and non-Muslim groups felt discriminated against and characterised the other group/s as receiving preference and/or better provision (Liebling, et. al., 2011).

- The vast majority of empirical research on religion in prisons and on prison chaplaincy includes exclusively or predominantly male research participants, both prison residents and prison chaplains. There is a real need for more research focused on women in prisons and in prison pastoral care. Our practitioner participants were all women (largely due to the contacts in place at MBIT amongst lay women) and our former prison residents were all men (largely due to the lower numbers and the difficulty of making contacts with this vulnerable population in a time of crisis due to the pandemic).

CST, Literature Analysis, and Participant Responses: Bringing it all Together

The central research questions of the Flourishing Inside project asked what could be learned about prison pastoral care from Catholic Social Thought, and how Catholic Social Thought could be enhanced by listening to the prison context. Bringing together the project’s three areas of enquiry, it is possible to chart the key themes arising from the literature and the participants in relation to most of the themes of CST:

| CST THEMES | PARTICIPANT THEMES | LITERATURE THEMES |

|---|---|---|

| Peace |

|

|

| Justice |

|

|

| Human dignity |

|

|

| Common good |

|

|

| Preferential option |

|

|

| Human rights |

|

|

| Solidarity |

|

|

| Family and community |

|

|

| Participation |

|

|

Put more succinctly, the following four core intersections of CST and prison chaplaincy have emerged:

- Recognition of the dignity of each person is central to prison chaplaincy.

- By creating bridges between those inside and outside prison, chaplains can contribute to the common good, participation in society, and connection with family and community.

- Through exercising critical presence, prison chaplains can seek justice and demonstrate the preferential option for those on the margins.

- As those within the system who are able to take time and pay attention, prison chaplains can cultivate peace, solidarity, and community.